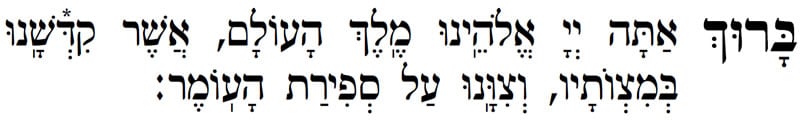

If you are counting at the beginning of the day after sundown, recite the following blessing before counting:

Baruch atah Adonai Eloheynu melech ha'olam

asher kid'shanu bemitz'vosav, vi'tzivanu al sefiras ha'Omer.

(Blessed are You, Hashem our G-d, Sovereign of the Universe,

Who has set us apart with His commandments and commanded us to count the Omer.)

May 12

4 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם תִּשְׁעָה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וַחֲמִשָּׁה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom tish'ah asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os va-chamishah yamim la'omer.

May 13

5 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם עֶשְׂרִים יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וְשִׁשָּׁה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom esrim yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os ve-shisha yamim la'omer.

May 13

5 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם עֶשְׂרִים יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וְשִׁשָּׁה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom esrim yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os ve-shisha yamim la'omer.

May 14

6 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם אֶחָד וְעֶשְׂרִים יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁלשָׁה שָׁבוּעוֹת לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom echad v-esrim yom,

sha'hem shloshah shavu'os la'omer.

May 14

6 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם אֶחָד וְעֶשְׂרִים יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁלשָׁה שָׁבוּעוֹת לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom echad v-esrim yom,

sha'hem shloshah shavu'os la'omer.

May 15

7 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שְׁנַֽיִם וְעֶשְׂרִים יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁלשָׁה שָׁבוּעוֹת וְיוֹם אֶחָד לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shnayim v-esrim yom,

sha'hem shloshah shavu'os ve-yom echad la'omer.

May 15

7 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שְׁנַֽיִם וְעֶשְׂרִים יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁלשָׁה שָׁבוּעוֹת וְיוֹם אֶחָד לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shnayim v-esrim yom,

sha'hem shloshah shavu'os ve-yom echad la'omer.

May 9

1 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שִׁשָּׁה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וּשְׁנֵי יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shishah-asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os u-shney yamim la'omer.

May 9

1 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שִׁשָּׁה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וּשְׁנֵי יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shishah-asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os u-shney yamim la'omer.

May 10

2 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שִׁבְעָה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וּשְׁלשָׁה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shiv'ah-asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os u-shloshah yamim la'omer.

May 10

2 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שִׁבְעָה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וּשְׁלשָׁה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shiv'ah-asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os u-shloshah yamim la'omer.

May 11

3 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שְׁמוֹנָה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וְאַרְבָּעָה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shmonah-asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os v-arba'ah yamim la'omer.

May 11

3 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם שְׁמוֹנָה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וְאַרְבָּעָה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom shmonah-asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os v-arba'ah yamim la'omer.

May 12

4 Iyar

Say:

הַיּוֹם תִּשְׁעָה עָשָׂר יוֹם שֶׁהֵם שְׁנֵי שָׁבוּעוֹת וַחֲמִשָּׁה יָמִים לָעֹֽמֶר

Ha-yom tish'ah asar yom,

sha'hem shney shavu'os va-chamishah yamim la'omer.

"And ye shall count for yourselves from the morrow after the sabbath, from the day that ye brought the sheaf of the wave offering; seven sabbath-weeks shall be complete. Even unto the morrow after the seventh sabbath-week shall ye count fifty days; and ye shall offer a new allegiance-offering unto Hashem."

Leviticus 23:15–16

Introduction

In Pirkei Avos (the Sayings of the Fathers), an ancient book of Jewish proverbs and maxims, there is a list of 48 qualities through which a man is shown to have full possession of the teachings of the Torah. A man who possesses these qualities is one who has readied himself to be fully prepared to receive the Torah, and to make full use of it.

So as we ready ourselves for Shavuos, the anniversary of the Giving of the Torah at Sinai, we will be taking these qualities one at a time, and pondering each one on a consecutive day of the Omer. After we list a particular quality, we will explain it a bit and give you something you can focus on in your daily life to improve your learning and practice.

“Greater is the Torah than the priesthood and than the kingship, seeing that the kingship is acquired with thirty distinctions [of honor], and the priesthood with twenty-four, but the Torah with forty-eight things, and they are these…”

— Pirkei Avos 6:5–6

Quality #15:

“Through reading [of Scripture]” (be-mikra)

Contemplation:

But as always, the specific nature of this qualification needs to be examined further. ‘Mikra’ does not mean ‘to read silently’. It means ‘to call aloud, to proclaim’. ‘Mikra’ became a short-hand way of referring to the Scripture because the Scripture was, from ancient times, that which was ‘read aloud in public’. The public reading of the Torah, the Prophets and the Writings was a way to ensure that everyone, even those without access to their own Torah scroll, would be able to read aloud and hear all the words of G-d regularly.

It was also a communal experience, which reminded each person that “the Torah is the inheritance of the community of Jacob” (Deuteronomy 33:4) and not his own individual personal possession to use in his own way. Over and over we are reminded that scholars ought not to study alone; partnership is the safeguard to preserving truth.

The principle of reading the Torah aloud is first mentioned in Deuteronomy 31:9–13, where the national head (in later generations, the king or the Nasi) is commanded to assemble the entire people every seven years at the Festival of Sukkos, to read the Torah to them. The men and the women would listen, and even the children who were too small to understand would learn from the awe-inspiring experience to fear G-d all their days. Joshua performed this practice after entering the Land (Joshua 8:30–35).

The king in Israel was commanded also to make a copy (or according to some reckonings, two copies) of the Torah from the original scroll of Moses which was kept by the Levite priests. “And it shall be with him, and he shall read aloud in it all the days of his life: that he may learn to fear the L-RD his God, to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them: That his heart be not lifted up above his brethren, and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand, or to the left: to the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom, he, and his children, in the midst of Israel.” (Deuteronomy 17:19–20)

After the Babylonian captivity came to an end, Ezra the priestly scribe fulfilled this commandment (Nehemiah 8:1–18), reading the entire Torah to the people over the course of the Festival. According to tradition, he also instituted the weekly reading of the Torah in the synagogues at that time, to inculcate further the Word of G-d into the hearts of the people, and it has remained a constant Jewish practice ever since his day.

“For Moses from generations of old in every city has those that proclaim him, being read in the synagogues every sabbath day.” (Acts 15:21) “Till I come, give focus to public reading, to exhortation, to instruction.” (1 Timothy 4:13)

Do not merely study silently or alone. Do not think that you can get by with only studying commentaries on Torah. There is no replacement for actually hearing and reading aloud the perfect and immortal Word of G-d. Get together with other Jews, and participate in the public reading of the Torah. That is how the Torah will become rooted in your memory.

Quality #16:

“Through repetition” (be-mishnah)

Contemplation:

Although it is known as the ‘Oral Teaching’, and was passed down in unwritten form for untold centuries, the work which we call The Mishnah was compiled and written down around 200 CE by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who collected almost all the teachings of the scholars of his day and unified them into a single body of text. There are six ‘orders’ or volumes that comprise the Mishnah, each of which is made up of several tractates covering different subjects.

So is that the message for today? That the way to fully acquire Torah is through studying the Mishnah? Perhaps that is not the fullest understanding of this principle.

The word ‘mishnah’ means ‘copy’ or ‘repetition’. It comes from the root sheni, meaning ‘second one’. The king of Israel, as we discussed yesterday, was commanded to write a copy (mishnah) of the Torah and to read from it every day. He could not merely use his father’s copy; he had to make one himself. The act of copying, letter by letter, was a way to further engrave the Torah in his memory.

When you see words on a page, you remember them only so much. When you hear them read while looking at them, you retain more. When you teach the subject to others, you retain even more. And when you copy out the teaching, taking care to match every letter, the exact wording of the teaching will be firmly fixed in your mind.

The other meaning of mishnah, ‘repetition’, is the reason that the orally-transmitted halacha is called The Mishnah: it was passed down through the generations by mouth, and it was essential that the student should be able to recall it word for word so that it would remain unaltered. Thus, the process of handing down the halacha was called ‘repetition’ (mishnah), and those who taught it were called Tanna'im (‘repeaters’ in the Aramaic language).

Repetition is a tried and true method of memorization, and it can assist a person to analyze what he learns more deeply by drawing attention to precise wording.

So how do you acquire Torah? Read it aloud, repeat it, make a verbal or even a written copy of it.

Quality #17:

“With a limited amount of traveling / business” (be-mi’ut sechorah)

Contemplation:

This is sound advice: we tend to devote the extra time we have to the thing which we consider most important in our lives, and for some people, that could be work. We even call it our ‘occupation’, that which occupies our days and our thoughts. But if our business employment is truly our ‘occupation’, we risk losing sight of the things that are truly important – the things which our employment is supposed to support, not replace. Our family, our service to others, our Torah study, and encompassing and driving all of these, our relationship with G-d. As Jews, our only real ‘occupation’ is supposed to be the study, dissemination and practice of G-d’s Word. Everything else is just a side venture, an offshoot business.

But remember, mi’ut only means “a little”. It doesn’t mean “nothing”. It would be wrong for us to forgo our business endeavors entirely, not because we need them to survive (G-d could provide for us without our going out to work each day), but because our business endeavors are another way of serving G-d and spreading the light of the Torah. G-d put us into the world and commanded us to work in it, to improve it and to preserve it: “And the L-RD G-d took the Man, and set him down in the garden of Eden to work it and to safeguard it.” (Genesis 2:15). Therefore, when we perform a needful task for a customer and put in a good day’s work for our employer, we are fulfilling this mandate to labor for the benefit of the world. Our actions also reflect on the people we represent, on the Book by which we live, and on the One Who gave it to us.

“Holding your manner of life honorably among the Gentiles: that, in the very thing where they speak against you as evildoers, [yet] having witnessed your good works they may glorify G-d in the day of reckoning.” (1 Peter 2:12) “…But we beseech you, brethren, that ye increase more and more; and that ye earnestly strive to be quiet, and to do your own business, and to work with your own hands, even as we commanded you, that ye may walk respectably toward those who are outside, and that ye may have lack of nothing.” (1 Thessalonians 4:10–12)

The same thing goes for traveling. Some people make a lifestyle out of traveling and seeing the world; others only travel when they have a specific need that requires them to go to another place. Too much travel can wear out the body, wear down the mind, and wear thin the bonds of fellowship with your community. Limitations in traveling, as in so many things, can be a real benefit. And yet, to stay in one place your whole life is to miss many things which can enrich your understanding, broaden your perspective of the Torah’s words, and enable you to serve a wider audience. If the Holy Temple was standing (may it be rebuilt speedily and in our days!), we would all need to make an effort to travel three times a year to Jerusalem. Traveling is in our blood: we began our existence as a nation by walking into the desert for forty years.

So we should have a moderate amount of business dealings, and traveling as well. But we should definitely have some of it. Another way of translating the principle for today is that Torah is acquired “with a little bit of business and traveling”. Keep in mind this facet of mi’ut. It will come in handy over the next few days.

“I have seen the occupation which G-d hath given to the sons of Man to be exercised in it. He hath made every thing beautiful in its time: also He hath set the hidden eternal future in their heart, without which no man can find out the work that G-d does from the beginning to the end. I know that there is nothing better for them, than for one to rejoice, and to do good in his life; and also that every person should eat and drink, and enjoy the good of all his labour; it is the gift of G-d.” (Ecclesiastes 3:10–13) “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? he shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before obscure men.” (Proverbs 22:29)

Quality #18:

“With a little bit of common courtesy” (be-mi’ut derech eretz)

Contemplation:

Derech Eretz as business activity and ‘secular knowledge’:

Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888) became widely known for his outlook on Jewish studies, which was embodied in the phrase, “Torah with derech eretz”. He did not invent the phrase or the concept behind it; it is as old as the times of R’ Yishmael in the Mishnah (150 CE). But he breathed new life into the idea and championed it fearlessly and with enthusiasm. Some people took “Torah with derech eretz” to mean “Torah with secular studies”, and claimed that R’ Hirsch was in favor of secular (business-oriented) education. Others believed that it was encouraging a lifestyle of studying Torah while simultaneously earning a living.

Was R’ Hirsch in favor of learning the Torah alongside of ‘secular’ education? To answer that, we need to know what he believed about ‘secularism’. He rejected the notion that a person could or should learn Torah as just one of many philosophical subjects or works of literature. He believed firmly that Torah was not only unique and utterly different from all ‘philosophy’ or ‘literature’, but that every philosophy or work of literature should only be studied in the light of the Torah’s frame of reference. Torah is to be the lens through which we view all other educational subjects.

But precisely because of this, R’ Hirsch believed that philosophy, physics, mathematics, astronomy, biology, history, linguistics, literature, the arts and all other subjects were not ‘secular’ in their nature at all. Each one of them needed to be taught and learned, provided that it was through a Torah-founded framework. If done properly, they would be Torah subjects, not secular ones.

This put him into contrast with some of the Torah-observant leaders of his day, who believed that scientific education was inherently anti-Torah. R’ Hirsch believed that all science, properly studied, would lead to the further glorification of G-d. So too would all forms of business: the Torah’s instructions are given to a people who would be involved in many types of work, and it was meant to apply to them all.

This worldview, which encompasses all ‘worldly’ activity within the Torah’s sphere and encourages its development within that sphere, is what “Torah with derech eretz” meant to R’ Hirsch. If a man has raised sons who became merchants and shopkeepers and farmers and scientists rather than rabbis, he can hold his head up proudly so long as they are G-d fearing, Torah-observant merchants, shopkeepers, farmers and scientists – for the world needs those just as much as it needs rabbis.

Derech Eretz as moral decency and courtesy:

Our sages elsewhere in Pirkei Avos say that “derech eretz preceded the Torah by two thousand years” (Avos 2:2). Our patriarchs had no body of written laws and teachings of G-d to which they could refer. Their service of G-d was through the practice of derech eretz, morally decent behavior. They exemplified traits such as lovingkindness and hospitality, truth and justice. They opened their tents to strangers; they fed people; they dealt honestly in their business; they stood up for the oppressed and vulnerable. They treated people with respect and courtesy, even when those people had wronged them. That was derech eretz.

Earlier in Pirkei Avos, R’ Elazar ben Azariah says, “If there is no Torah, there is no derech eretz. If there is no derech eretz, there is no Torah.” (Avos 3:21) If a person has studied and become learned, what good does it do him unless he behaves in a decent, courteous and moral fashion? And if a person wishes to behave morally, how will he know the specifics of what to do and what to avoid, if he does not learn Torah? Torah and derech eretz truly go hand in hand.

Therefore, when the sages say here in Pirkei Avos that Torah is acquired with mi’ut derech eretz, it may be that they are warning not to let our sense of proportion slip. Our Torah study must constantly be seasoned with a bit of courtesy and decent behavior. Don’t get so wrapped up in your study that you fail to behave pleasantly with other people.

“One should always strive to be on the best terms with his brethren and his relatives and with all men and even with the heathen in the street, in order that he may be beloved above and well-liked below and be acceptable to his fellow creatures. It was related of R’ Yochanan ben Zakkai that no man ever gave him greeting first [without him pre-empting them], even a heathen in the street.” (Gemara, Berachos 17a) “Recompense to no man evil for evil. Provide things admirable in the sight of all men. If it be possible, as much as lies in your own selves, live in harmony with all men.” (Romans 12:17–18)

Quality #19:

“With a little bit of pleasure / enjoyment” (be-mi’ut ta’anug)

Contemplation:

The word for “enjoyment” here comes from the root oneg, meaning pleasure or delight, or a delicacy, perhaps of food. The concept of oneg is most well known to us from its preeminence during Shabbos. Oneg Shabbos (the enjoyment / pleasure of Shabbos) is an essential part of celebrating the holy day. G-d Himself tells us to “call the Sabbath a delight (oneg)” (Isaiah 58:13). We do so in part by eating rich foods and delicacies, and engaging in other activities which bring delight to our Shabbos table such as singing zemiros (songs, hymns).

Since we set aside Shabbos as a time for oneg, it is only proper that we should not indulge constantly in it during the rest of the week. Pleasures which are indulged in every day soon cease to be special. It is also a well known medical fact that constant eating of delicacies is bad for your health. In this context, “a limited amount of pleasure / delicacies” seems to be sound advice. If the body is unhealthy, the mind will also have difficulty focusing and learning.

But remember, a little is not the same as nothing. We may not omit oneg from our lives altogether. Today’s lesson cautions us against asceticism as well as hedonism. We are supposed to take our learning with “a little bit of enjoyment” from time to time.

Quality #15:

“Through reading [of Scripture]” (be-mikra)

Contemplation:

But as always, the specific nature of this qualification needs to be examined further. ‘Mikra’ does not mean ‘to read silently’. It means ‘to call aloud, to proclaim’. ‘Mikra’ became a short-hand way of referring to the Scripture because the Scripture was, from ancient times, that which was ‘read aloud in public’. The public reading of the Torah, the Prophets and the Writings was a way to ensure that everyone, even those without access to their own Torah scroll, would be able to read aloud and hear all the words of G-d regularly.

It was also a communal experience, which reminded each person that “the Torah is the inheritance of the community of Jacob” (Deuteronomy 33:4) and not his own individual personal possession to use in his own way. Over and over we are reminded that scholars ought not to study alone; partnership is the safeguard to preserving truth.

The principle of reading the Torah aloud is first mentioned in Deuteronomy 31:9–13, where the national head (in later generations, the king or the Nasi) is commanded to assemble the entire people every seven years at the Festival of Sukkos, to read the Torah to them. The men and the women would listen, and even the children who were too small to understand would learn from the awe-inspiring experience to fear G-d all their days. Joshua performed this practice after entering the Land (Joshua 8:30–35).

The king in Israel was commanded also to make a copy (or according to some reckonings, two copies) of the Torah from the original scroll of Moses which was kept by the Levite priests. “And it shall be with him, and he shall read aloud in it all the days of his life: that he may learn to fear the L-RD his God, to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them: That his heart be not lifted up above his brethren, and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand, or to the left: to the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom, he, and his children, in the midst of Israel.” (Deuteronomy 17:19–20)

After the Babylonian captivity came to an end, Ezra the priestly scribe fulfilled this commandment (Nehemiah 8:1–18), reading the entire Torah to the people over the course of the Festival. According to tradition, he also instituted the weekly reading of the Torah in the synagogues at that time, to inculcate further the Word of G-d into the hearts of the people, and it has remained a constant Jewish practice ever since his day.

“For Moses from generations of old in every city has those that proclaim him, being read in the synagogues every sabbath day.” (Acts 15:21) “Till I come, give focus to public reading, to exhortation, to instruction.” (1 Timothy 4:13)

Do not merely study silently or alone. Do not think that you can get by with only studying commentaries on Torah. There is no replacement for actually hearing and reading aloud the perfect and immortal Word of G-d. Get together with other Jews, and participate in the public reading of the Torah. That is how the Torah will become rooted in your memory.

Quality #16:

“Through repetition” (be-mishnah)

Contemplation:

Although it is known as the ‘Oral Teaching’, and was passed down in unwritten form for untold centuries, the work which we call The Mishnah was compiled and written down around 200 CE by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who collected almost all the teachings of the scholars of his day and unified them into a single body of text. There are six ‘orders’ or volumes that comprise the Mishnah, each of which is made up of several tractates covering different subjects.

So is that the message for today? That the way to fully acquire Torah is through studying the Mishnah? Perhaps that is not the fullest understanding of this principle.

The word ‘mishnah’ means ‘copy’ or ‘repetition’. It comes from the root sheni, meaning ‘second one’. The king of Israel, as we discussed yesterday, was commanded to write a copy (mishnah) of the Torah and to read from it every day. He could not merely use his father’s copy; he had to make one himself. The act of copying, letter by letter, was a way to further engrave the Torah in his memory.

When you see words on a page, you remember them only so much. When you hear them read while looking at them, you retain more. When you teach the subject to others, you retain even more. And when you copy out the teaching, taking care to match every letter, the exact wording of the teaching will be firmly fixed in your mind.

The other meaning of mishnah, ‘repetition’, is the reason that the orally-transmitted halacha is called The Mishnah: it was passed down through the generations by mouth, and it was essential that the student should be able to recall it word for word so that it would remain unaltered. Thus, the process of handing down the halacha was called ‘repetition’ (mishnah), and those who taught it were called Tanna'im (‘repeaters’ in the Aramaic language).

Repetition is a tried and true method of memorization, and it can assist a person to analyze what he learns more deeply by drawing attention to precise wording.

So how do you acquire Torah? Read it aloud, repeat it, make a verbal or even a written copy of it.

Quality #17:

“With a limited amount of traveling / business” (be-mi’ut sechorah)

Contemplation:

This is sound advice: we tend to devote the extra time we have to the thing which we consider most important in our lives, and for some people, that could be work. We even call it our ‘occupation’, that which occupies our days and our thoughts. But if our business employment is truly our ‘occupation’, we risk losing sight of the things that are truly important – the things which our employment is supposed to support, not replace. Our family, our service to others, our Torah study, and encompassing and driving all of these, our relationship with G-d. As Jews, our only real ‘occupation’ is supposed to be the study, dissemination and practice of G-d’s Word. Everything else is just a side venture, an offshoot business.

But remember, mi’ut only means “a little”. It doesn’t mean “nothing”. It would be wrong for us to forgo our business endeavors entirely, not because we need them to survive (G-d could provide for us without our going out to work each day), but because our business endeavors are another way of serving G-d and spreading the light of the Torah. G-d put us into the world and commanded us to work in it, to improve it and to preserve it: “And the L-RD G-d took the Man, and set him down in the garden of Eden to work it and to safeguard it.” (Genesis 2:15). Therefore, when we perform a needful task for a customer and put in a good day’s work for our employer, we are fulfilling this mandate to labor for the benefit of the world. Our actions also reflect on the people we represent, on the Book by which we live, and on the One Who gave it to us.

“Holding your manner of life honorably among the Gentiles: that, in the very thing where they speak against you as evildoers, [yet] having witnessed your good works they may glorify G-d in the day of reckoning.” (1 Peter 2:12) “…But we beseech you, brethren, that ye increase more and more; and that ye earnestly strive to be quiet, and to do your own business, and to work with your own hands, even as we commanded you, that ye may walk respectably toward those who are outside, and that ye may have lack of nothing.” (1 Thessalonians 4:10–12)

The same thing goes for traveling. Some people make a lifestyle out of traveling and seeing the world; others only travel when they have a specific need that requires them to go to another place. Too much travel can wear out the body, wear down the mind, and wear thin the bonds of fellowship with your community. Limitations in traveling, as in so many things, can be a real benefit. And yet, to stay in one place your whole life is to miss many things which can enrich your understanding, broaden your perspective of the Torah’s words, and enable you to serve a wider audience. If the Holy Temple was standing (may it be rebuilt speedily and in our days!), we would all need to make an effort to travel three times a year to Jerusalem. Traveling is in our blood: we began our existence as a nation by walking into the desert for forty years.

So we should have a moderate amount of business dealings, and traveling as well. But we should definitely have some of it. Another way of translating the principle for today is that Torah is acquired “with a little bit of business and traveling”. Keep in mind this facet of mi’ut. It will come in handy over the next few days.

“I have seen the occupation which G-d hath given to the sons of Man to be exercised in it. He hath made every thing beautiful in its time: also He hath set the hidden eternal future in their heart, without which no man can find out the work that G-d does from the beginning to the end. I know that there is nothing better for them, than for one to rejoice, and to do good in his life; and also that every person should eat and drink, and enjoy the good of all his labour; it is the gift of G-d.” (Ecclesiastes 3:10–13) “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? he shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before obscure men.” (Proverbs 22:29)

Quality #18:

“With a little bit of common courtesy” (be-mi’ut derech eretz)

Contemplation:

Derech Eretz as business activity and ‘secular knowledge’:

Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888) became widely known for his outlook on Jewish studies, which was embodied in the phrase, “Torah with derech eretz”. He did not invent the phrase or the concept behind it; it is as old as the times of R’ Yishmael in the Mishnah (150 CE). But he breathed new life into the idea and championed it fearlessly and with enthusiasm. Some people took “Torah with derech eretz” to mean “Torah with secular studies”, and claimed that R’ Hirsch was in favor of secular (business-oriented) education. Others believed that it was encouraging a lifestyle of studying Torah while simultaneously earning a living.

Was R’ Hirsch in favor of learning the Torah alongside of ‘secular’ education? To answer that, we need to know what he believed about ‘secularism’. He rejected the notion that a person could or should learn Torah as just one of many philosophical subjects or works of literature. He believed firmly that Torah was not only unique and utterly different from all ‘philosophy’ or ‘literature’, but that every philosophy or work of literature should only be studied in the light of the Torah’s frame of reference. Torah is to be the lens through which we view all other educational subjects.

But precisely because of this, R’ Hirsch believed that philosophy, physics, mathematics, astronomy, biology, history, linguistics, literature, the arts and all other subjects were not ‘secular’ in their nature at all. Each one of them needed to be taught and learned, provided that it was through a Torah-founded framework. If done properly, they would be Torah subjects, not secular ones.

This put him into contrast with some of the Torah-observant leaders of his day, who believed that scientific education was inherently anti-Torah. R’ Hirsch believed that all science, properly studied, would lead to the further glorification of G-d. So too would all forms of business: the Torah’s instructions are given to a people who would be involved in many types of work, and it was meant to apply to them all.

This worldview, which encompasses all ‘worldly’ activity within the Torah’s sphere and encourages its development within that sphere, is what “Torah with derech eretz” meant to R’ Hirsch. If a man has raised sons who became merchants and shopkeepers and farmers and scientists rather than rabbis, he can hold his head up proudly so long as they are G-d fearing, Torah-observant merchants, shopkeepers, farmers and scientists – for the world needs those just as much as it needs rabbis.

Derech Eretz as moral decency and courtesy:

Our sages elsewhere in Pirkei Avos say that “derech eretz preceded the Torah by two thousand years” (Avos 2:2). Our patriarchs had no body of written laws and teachings of G-d to which they could refer. Their service of G-d was through the practice of derech eretz, morally decent behavior. They exemplified traits such as lovingkindness and hospitality, truth and justice. They opened their tents to strangers; they fed people; they dealt honestly in their business; they stood up for the oppressed and vulnerable. They treated people with respect and courtesy, even when those people had wronged them. That was derech eretz.

Earlier in Pirkei Avos, R’ Elazar ben Azariah says, “If there is no Torah, there is no derech eretz. If there is no derech eretz, there is no Torah.” (Avos 3:21) If a person has studied and become learned, what good does it do him unless he behaves in a decent, courteous and moral fashion? And if a person wishes to behave morally, how will he know the specifics of what to do and what to avoid, if he does not learn Torah? Torah and derech eretz truly go hand in hand.

Therefore, when the sages say here in Pirkei Avos that Torah is acquired with mi’ut derech eretz, it may be that they are warning not to let our sense of proportion slip. Our Torah study must constantly be seasoned with a bit of courtesy and decent behavior. Don’t get so wrapped up in your study that you fail to behave pleasantly with other people.

“One should always strive to be on the best terms with his brethren and his relatives and with all men and even with the heathen in the street, in order that he may be beloved above and well-liked below and be acceptable to his fellow creatures. It was related of R’ Yochanan ben Zakkai that no man ever gave him greeting first [without him pre-empting them], even a heathen in the street.” (Gemara, Berachos 17a) “Recompense to no man evil for evil. Provide things admirable in the sight of all men. If it be possible, as much as lies in your own selves, live in harmony with all men.” (Romans 12:17–18)

Quality #19:

“With a little bit of pleasure / enjoyment” (be-mi’ut ta’anug)

Contemplation:

The word for “enjoyment” here comes from the root oneg, meaning pleasure or delight, or a delicacy, perhaps of food. The concept of oneg is most well known to us from its preeminence during Shabbos. Oneg Shabbos (the enjoyment / pleasure of Shabbos) is an essential part of celebrating the holy day. G-d Himself tells us to “call the Sabbath a delight (oneg)” (Isaiah 58:13). We do so in part by eating rich foods and delicacies, and engaging in other activities which bring delight to our Shabbos table such as singing zemiros (songs, hymns).

Since we set aside Shabbos as a time for oneg, it is only proper that we should not indulge constantly in it during the rest of the week. Pleasures which are indulged in every day soon cease to be special. It is also a well known medical fact that constant eating of delicacies is bad for your health. In this context, “a limited amount of pleasure / delicacies” seems to be sound advice. If the body is unhealthy, the mind will also have difficulty focusing and learning.

But remember, a little is not the same as nothing. We may not omit oneg from our lives altogether. Today’s lesson cautions us against asceticism as well as hedonism. We are supposed to take our learning with “a little bit of enjoyment” from time to time.

Quality #20:

“With a little bit of sleep” (be-mi’ut shenah)

(With acknowledgements and gratitude to Rabbi Avraham J. Twerski, from whose book, ‘Visions of the Fathers’, large portions of tonight’s commentary were drawn.)

Contemplation:

Yet on the other hand, too much sleep can detract from your mental sharpness as well. Rising early in the morning is not simply a laudable practice associated with industriousness and diligence; it is also a healthy time to wake up. Your body and mind will feel clearer and more rested if you make a habit of rising early, and it is the perfect time to spend studying some Torah before anything else intrudes on your day.

Some Torah scholars are famous for having slept barely at all. The Vilna Gaon, a prodigious genius and a giant in the Torah world, slept an average of twenty minutes in a day, in a series of catnaps. He used to keep a bucket of cold water by his feet while studying, so that if he started to feel drowsy, he would put his feet into the water to help himself stay alert, so intent was he on not wasting a moment when he could be studying Torah. Was he damaging his health by acting this way? Or are we all required to follow his example?

The Tzaddik of Sanz, another rabbi who slept very little, offered the following explanation for his unusual behavior: “A swift runner may cover a long distance in a fraction of the time it would take the average person to travel that far. I happen to be a swift sleeper. I can accomplish in minutes of sleep what may take others hours.”

We may all have experienced, at one time or another, a night of little sleep which nevertheless left us feeling refreshed upon waking. Sometimes, a little sleep accomplishes more than we expect it to. In modern scientific jargon, the REM (rapid-eye-movement) phase of sleep is believed to be the most important part of a night’s rest, and the length of time it takes for the body to enter REM sleep (sometimes several hours) is the most critical factor in determining how long the night’s rest needs to be. If a person could enter REM sleep immediately upon falling asleep, he could theoretically be refreshed with far fewer hours of sleep.

This is what the Tzaddik of Sanz meant. Such a rigorous schedule as the Vilna Gaon’s is not meant for everyone nor would it be healthy for everyone; only a very few people may find that they have been gifted, genetically or otherwise, with less of a need for sleep. The important thing is that, once a person has had enough sleep to be refreshed, he does not develop a habit of lying in bed longer than he has to. This habit of indolence leads to poverty, both physical and mental:

“By the field of the slothful man I passed, and by the vineyard of the person lacking heart. And, lo, it was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered its surface, and its stone wall was broken down. Then I saw, and I myself applied it to my own heart: I looked, and I received correction. ‘A little sleep (m’at shenot), a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to lie down’: and your poverty shall come walking along, and your want as an armed man.” (Proverbs 24:30–34)

Here, “a little sleep” is used in the words of the slothful man, to indicate his plea for ‘just a little more sleep’. A ‘little more’ is open-ended. No matter how much he has, he always wants ‘a little more’. That is the sign of an addiction. In all the instances we have looked at where the word mi’ut is used, it refers to moderation and keeping something in its proper proportion. To become addicted to anything, whether it be work, pleasure, worldly business, or sleep, is to surrender our freedom of moral choice and to become slaves to a passion or a habit.

So by all means, ‘have a little snooze’. Especially on Shabbos, it is appropriate and right to take one’s rest and be refreshed from the week’s labors. But remain master of yourself. Don’t let idleness become your default position. If you have duties that require your presence, bestir yourself and don’t neglect them. Timeliness and industriousness are qualities that mark a good student of Torah. Build into your life an aversion to procrastination and an enthusiasm for actively performing mitzvos, and you will have come a long way towards grasping the Torah in your own life.

Quality #15:

“Through reading [of Scripture]” (be-mikra)

Contemplation:

But as always, the specific nature of this qualification needs to be examined further. ‘Mikra’ does not mean ‘to read silently’. It means ‘to call aloud, to proclaim’. ‘Mikra’ became a short-hand way of referring to the Scripture because the Scripture was, from ancient times, that which was ‘read aloud in public’. The public reading of the Torah, the Prophets and the Writings was a way to ensure that everyone, even those without access to their own Torah scroll, would be able to read aloud and hear all the words of G-d regularly.

It was also a communal experience, which reminded each person that “the Torah is the inheritance of the community of Jacob” (Deuteronomy 33:4) and not his own individual personal possession to use in his own way. Over and over we are reminded that scholars ought not to study alone; partnership is the safeguard to preserving truth.

The principle of reading the Torah aloud is first mentioned in Deuteronomy 31:9–13, where the national head (in later generations, the king or the Nasi) is commanded to assemble the entire people every seven years at the Festival of Sukkos, to read the Torah to them. The men and the women would listen, and even the children who were too small to understand would learn from the awe-inspiring experience to fear G-d all their days. Joshua performed this practice after entering the Land (Joshua 8:30–35).

The king in Israel was commanded also to make a copy (or according to some reckonings, two copies) of the Torah from the original scroll of Moses which was kept by the Levite priests. “And it shall be with him, and he shall read aloud in it all the days of his life: that he may learn to fear the L-RD his God, to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them: That his heart be not lifted up above his brethren, and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand, or to the left: to the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom, he, and his children, in the midst of Israel.” (Deuteronomy 17:19–20)

After the Babylonian captivity came to an end, Ezra the priestly scribe fulfilled this commandment (Nehemiah 8:1–18), reading the entire Torah to the people over the course of the Festival. According to tradition, he also instituted the weekly reading of the Torah in the synagogues at that time, to inculcate further the Word of G-d into the hearts of the people, and it has remained a constant Jewish practice ever since his day.

“For Moses from generations of old in every city has those that proclaim him, being read in the synagogues every sabbath day.” (Acts 15:21) “Till I come, give focus to public reading, to exhortation, to instruction.” (1 Timothy 4:13)

Do not merely study silently or alone. Do not think that you can get by with only studying commentaries on Torah. There is no replacement for actually hearing and reading aloud the perfect and immortal Word of G-d. Get together with other Jews, and participate in the public reading of the Torah. That is how the Torah will become rooted in your memory.

Quality #16:

“Through repetition” (be-mishnah)

Contemplation:

Although it is known as the ‘Oral Teaching’, and was passed down in unwritten form for untold centuries, the work which we call The Mishnah was compiled and written down around 200 CE by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who collected almost all the teachings of the scholars of his day and unified them into a single body of text. There are six ‘orders’ or volumes that comprise the Mishnah, each of which is made up of several tractates covering different subjects.

So is that the message for today? That the way to fully acquire Torah is through studying the Mishnah? Perhaps that is not the fullest understanding of this principle.

The word ‘mishnah’ means ‘copy’ or ‘repetition’. It comes from the root sheni, meaning ‘second one’. The king of Israel, as we discussed yesterday, was commanded to write a copy (mishnah) of the Torah and to read from it every day. He could not merely use his father’s copy; he had to make one himself. The act of copying, letter by letter, was a way to further engrave the Torah in his memory.

When you see words on a page, you remember them only so much. When you hear them read while looking at them, you retain more. When you teach the subject to others, you retain even more. And when you copy out the teaching, taking care to match every letter, the exact wording of the teaching will be firmly fixed in your mind.

The other meaning of mishnah, ‘repetition’, is the reason that the orally-transmitted halacha is called The Mishnah: it was passed down through the generations by mouth, and it was essential that the student should be able to recall it word for word so that it would remain unaltered. Thus, the process of handing down the halacha was called ‘repetition’ (mishnah), and those who taught it were called Tanna'im (‘repeaters’ in the Aramaic language).

Repetition is a tried and true method of memorization, and it can assist a person to analyze what he learns more deeply by drawing attention to precise wording.

So how do you acquire Torah? Read it aloud, repeat it, make a verbal or even a written copy of it.

Quality #17:

“With a limited amount of traveling / business” (be-mi’ut sechorah)

Contemplation:

This is sound advice: we tend to devote the extra time we have to the thing which we consider most important in our lives, and for some people, that could be work. We even call it our ‘occupation’, that which occupies our days and our thoughts. But if our business employment is truly our ‘occupation’, we risk losing sight of the things that are truly important – the things which our employment is supposed to support, not replace. Our family, our service to others, our Torah study, and encompassing and driving all of these, our relationship with G-d. As Jews, our only real ‘occupation’ is supposed to be the study, dissemination and practice of G-d’s Word. Everything else is just a side venture, an offshoot business.

But remember, mi’ut only means “a little”. It doesn’t mean “nothing”. It would be wrong for us to forgo our business endeavors entirely, not because we need them to survive (G-d could provide for us without our going out to work each day), but because our business endeavors are another way of serving G-d and spreading the light of the Torah. G-d put us into the world and commanded us to work in it, to improve it and to preserve it: “And the L-RD G-d took the Man, and set him down in the garden of Eden to work it and to safeguard it.” (Genesis 2:15). Therefore, when we perform a needful task for a customer and put in a good day’s work for our employer, we are fulfilling this mandate to labor for the benefit of the world. Our actions also reflect on the people we represent, on the Book by which we live, and on the One Who gave it to us.

“Holding your manner of life honorably among the Gentiles: that, in the very thing where they speak against you as evildoers, [yet] having witnessed your good works they may glorify G-d in the day of reckoning.” (1 Peter 2:12) “…But we beseech you, brethren, that ye increase more and more; and that ye earnestly strive to be quiet, and to do your own business, and to work with your own hands, even as we commanded you, that ye may walk respectably toward those who are outside, and that ye may have lack of nothing.” (1 Thessalonians 4:10–12)

The same thing goes for traveling. Some people make a lifestyle out of traveling and seeing the world; others only travel when they have a specific need that requires them to go to another place. Too much travel can wear out the body, wear down the mind, and wear thin the bonds of fellowship with your community. Limitations in traveling, as in so many things, can be a real benefit. And yet, to stay in one place your whole life is to miss many things which can enrich your understanding, broaden your perspective of the Torah’s words, and enable you to serve a wider audience. If the Holy Temple was standing (may it be rebuilt speedily and in our days!), we would all need to make an effort to travel three times a year to Jerusalem. Traveling is in our blood: we began our existence as a nation by walking into the desert for forty years.

So we should have a moderate amount of business dealings, and traveling as well. But we should definitely have some of it. Another way of translating the principle for today is that Torah is acquired “with a little bit of business and traveling”. Keep in mind this facet of mi’ut. It will come in handy over the next few days.

“I have seen the occupation which G-d hath given to the sons of Man to be exercised in it. He hath made every thing beautiful in its time: also He hath set the hidden eternal future in their heart, without which no man can find out the work that G-d does from the beginning to the end. I know that there is nothing better for them, than for one to rejoice, and to do good in his life; and also that every person should eat and drink, and enjoy the good of all his labour; it is the gift of G-d.” (Ecclesiastes 3:10–13) “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? he shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before obscure men.” (Proverbs 22:29)

Quality #18:

“With a little bit of common courtesy” (be-mi’ut derech eretz)

Contemplation:

Derech Eretz as business activity and ‘secular knowledge’:

Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888) became widely known for his outlook on Jewish studies, which was embodied in the phrase, “Torah with derech eretz”. He did not invent the phrase or the concept behind it; it is as old as the times of R’ Yishmael in the Mishnah (150 CE). But he breathed new life into the idea and championed it fearlessly and with enthusiasm. Some people took “Torah with derech eretz” to mean “Torah with secular studies”, and claimed that R’ Hirsch was in favor of secular (business-oriented) education. Others believed that it was encouraging a lifestyle of studying Torah while simultaneously earning a living.

Was R’ Hirsch in favor of learning the Torah alongside of ‘secular’ education? To answer that, we need to know what he believed about ‘secularism’. He rejected the notion that a person could or should learn Torah as just one of many philosophical subjects or works of literature. He believed firmly that Torah was not only unique and utterly different from all ‘philosophy’ or ‘literature’, but that every philosophy or work of literature should only be studied in the light of the Torah’s frame of reference. Torah is to be the lens through which we view all other educational subjects.

But precisely because of this, R’ Hirsch believed that philosophy, physics, mathematics, astronomy, biology, history, linguistics, literature, the arts and all other subjects were not ‘secular’ in their nature at all. Each one of them needed to be taught and learned, provided that it was through a Torah-founded framework. If done properly, they would be Torah subjects, not secular ones.

This put him into contrast with some of the Torah-observant leaders of his day, who believed that scientific education was inherently anti-Torah. R’ Hirsch believed that all science, properly studied, would lead to the further glorification of G-d. So too would all forms of business: the Torah’s instructions are given to a people who would be involved in many types of work, and it was meant to apply to them all.

This worldview, which encompasses all ‘worldly’ activity within the Torah’s sphere and encourages its development within that sphere, is what “Torah with derech eretz” meant to R’ Hirsch. If a man has raised sons who became merchants and shopkeepers and farmers and scientists rather than rabbis, he can hold his head up proudly so long as they are G-d fearing, Torah-observant merchants, shopkeepers, farmers and scientists – for the world needs those just as much as it needs rabbis.

Derech Eretz as moral decency and courtesy:

Our sages elsewhere in Pirkei Avos say that “derech eretz preceded the Torah by two thousand years” (Avos 2:2). Our patriarchs had no body of written laws and teachings of G-d to which they could refer. Their service of G-d was through the practice of derech eretz, morally decent behavior. They exemplified traits such as lovingkindness and hospitality, truth and justice. They opened their tents to strangers; they fed people; they dealt honestly in their business; they stood up for the oppressed and vulnerable. They treated people with respect and courtesy, even when those people had wronged them. That was derech eretz.

Earlier in Pirkei Avos, R’ Elazar ben Azariah says, “If there is no Torah, there is no derech eretz. If there is no derech eretz, there is no Torah.” (Avos 3:21) If a person has studied and become learned, what good does it do him unless he behaves in a decent, courteous and moral fashion? And if a person wishes to behave morally, how will he know the specifics of what to do and what to avoid, if he does not learn Torah? Torah and derech eretz truly go hand in hand.

Therefore, when the sages say here in Pirkei Avos that Torah is acquired with mi’ut derech eretz, it may be that they are warning not to let our sense of proportion slip. Our Torah study must constantly be seasoned with a bit of courtesy and decent behavior. Don’t get so wrapped up in your study that you fail to behave pleasantly with other people.

“One should always strive to be on the best terms with his brethren and his relatives and with all men and even with the heathen in the street, in order that he may be beloved above and well-liked below and be acceptable to his fellow creatures. It was related of R’ Yochanan ben Zakkai that no man ever gave him greeting first [without him pre-empting them], even a heathen in the street.” (Gemara, Berachos 17a) “Recompense to no man evil for evil. Provide things admirable in the sight of all men. If it be possible, as much as lies in your own selves, live in harmony with all men.” (Romans 12:17–18)

Quality #19:

“With a little bit of pleasure / enjoyment” (be-mi’ut ta’anug)

Contemplation:

The word for “enjoyment” here comes from the root oneg, meaning pleasure or delight, or a delicacy, perhaps of food. The concept of oneg is most well known to us from its preeminence during Shabbos. Oneg Shabbos (the enjoyment / pleasure of Shabbos) is an essential part of celebrating the holy day. G-d Himself tells us to “call the Sabbath a delight (oneg)” (Isaiah 58:13). We do so in part by eating rich foods and delicacies, and engaging in other activities which bring delight to our Shabbos table such as singing zemiros (songs, hymns).

Since we set aside Shabbos as a time for oneg, it is only proper that we should not indulge constantly in it during the rest of the week. Pleasures which are indulged in every day soon cease to be special. It is also a well known medical fact that constant eating of delicacies is bad for your health. In this context, “a limited amount of pleasure / delicacies” seems to be sound advice. If the body is unhealthy, the mind will also have difficulty focusing and learning.

But remember, a little is not the same as nothing. We may not omit oneg from our lives altogether. Today’s lesson cautions us against asceticism as well as hedonism. We are supposed to take our learning with “a little bit of enjoyment” from time to time.

Quality #20:

“With a little bit of sleep” (be-mi’ut shenah)

(With acknowledgements and gratitude to Rabbi Avraham J. Twerski, from whose book, ‘Visions of the Fathers’, large portions of tonight’s commentary were drawn.)

Contemplation:

Yet on the other hand, too much sleep can detract from your mental sharpness as well. Rising early in the morning is not simply a laudable practice associated with industriousness and diligence; it is also a healthy time to wake up. Your body and mind will feel clearer and more rested if you make a habit of rising early, and it is the perfect time to spend studying some Torah before anything else intrudes on your day.

Some Torah scholars are famous for having slept barely at all. The Vilna Gaon, a prodigious genius and a giant in the Torah world, slept an average of twenty minutes in a day, in a series of catnaps. He used to keep a bucket of cold water by his feet while studying, so that if he started to feel drowsy, he would put his feet into the water to help himself stay alert, so intent was he on not wasting a moment when he could be studying Torah. Was he damaging his health by acting this way? Or are we all required to follow his example?

The Tzaddik of Sanz, another rabbi who slept very little, offered the following explanation for his unusual behavior: “A swift runner may cover a long distance in a fraction of the time it would take the average person to travel that far. I happen to be a swift sleeper. I can accomplish in minutes of sleep what may take others hours.”

We may all have experienced, at one time or another, a night of little sleep which nevertheless left us feeling refreshed upon waking. Sometimes, a little sleep accomplishes more than we expect it to. In modern scientific jargon, the REM (rapid-eye-movement) phase of sleep is believed to be the most important part of a night’s rest, and the length of time it takes for the body to enter REM sleep (sometimes several hours) is the most critical factor in determining how long the night’s rest needs to be. If a person could enter REM sleep immediately upon falling asleep, he could theoretically be refreshed with far fewer hours of sleep.

This is what the Tzaddik of Sanz meant. Such a rigorous schedule as the Vilna Gaon’s is not meant for everyone nor would it be healthy for everyone; only a very few people may find that they have been gifted, genetically or otherwise, with less of a need for sleep. The important thing is that, once a person has had enough sleep to be refreshed, he does not develop a habit of lying in bed longer than he has to. This habit of indolence leads to poverty, both physical and mental:

“By the field of the slothful man I passed, and by the vineyard of the person lacking heart. And, lo, it was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered its surface, and its stone wall was broken down. Then I saw, and I myself applied it to my own heart: I looked, and I received correction. ‘A little sleep (m’at shenot), a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to lie down’: and your poverty shall come walking along, and your want as an armed man.” (Proverbs 24:30–34)

Here, “a little sleep” is used in the words of the slothful man, to indicate his plea for ‘just a little more sleep’. A ‘little more’ is open-ended. No matter how much he has, he always wants ‘a little more’. That is the sign of an addiction. In all the instances we have looked at where the word mi’ut is used, it refers to moderation and keeping something in its proper proportion. To become addicted to anything, whether it be work, pleasure, worldly business, or sleep, is to surrender our freedom of moral choice and to become slaves to a passion or a habit.

So by all means, ‘have a little snooze’. Especially on Shabbos, it is appropriate and right to take one’s rest and be refreshed from the week’s labors. But remain master of yourself. Don’t let idleness become your default position. If you have duties that require your presence, bestir yourself and don’t neglect them. Timeliness and industriousness are qualities that mark a good student of Torah. Build into your life an aversion to procrastination and an enthusiasm for actively performing mitzvos, and you will have come a long way towards grasping the Torah in your own life.

Quality #15:

“Through reading [of Scripture]” (be-mikra)

Contemplation:

But as always, the specific nature of this qualification needs to be examined further. ‘Mikra’ does not mean ‘to read silently’. It means ‘to call aloud, to proclaim’. ‘Mikra’ became a short-hand way of referring to the Scripture because the Scripture was, from ancient times, that which was ‘read aloud in public’. The public reading of the Torah, the Prophets and the Writings was a way to ensure that everyone, even those without access to their own Torah scroll, would be able to read aloud and hear all the words of G-d regularly.

It was also a communal experience, which reminded each person that “the Torah is the inheritance of the community of Jacob” (Deuteronomy 33:4) and not his own individual personal possession to use in his own way. Over and over we are reminded that scholars ought not to study alone; partnership is the safeguard to preserving truth.

The principle of reading the Torah aloud is first mentioned in Deuteronomy 31:9–13, where the national head (in later generations, the king or the Nasi) is commanded to assemble the entire people every seven years at the Festival of Sukkos, to read the Torah to them. The men and the women would listen, and even the children who were too small to understand would learn from the awe-inspiring experience to fear G-d all their days. Joshua performed this practice after entering the Land (Joshua 8:30–35).

The king in Israel was commanded also to make a copy (or according to some reckonings, two copies) of the Torah from the original scroll of Moses which was kept by the Levite priests. “And it shall be with him, and he shall read aloud in it all the days of his life: that he may learn to fear the L-RD his God, to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them: That his heart be not lifted up above his brethren, and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand, or to the left: to the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom, he, and his children, in the midst of Israel.” (Deuteronomy 17:19–20)

After the Babylonian captivity came to an end, Ezra the priestly scribe fulfilled this commandment (Nehemiah 8:1–18), reading the entire Torah to the people over the course of the Festival. According to tradition, he also instituted the weekly reading of the Torah in the synagogues at that time, to inculcate further the Word of G-d into the hearts of the people, and it has remained a constant Jewish practice ever since his day.

“For Moses from generations of old in every city has those that proclaim him, being read in the synagogues every sabbath day.” (Acts 15:21) “Till I come, give focus to public reading, to exhortation, to instruction.” (1 Timothy 4:13)

Do not merely study silently or alone. Do not think that you can get by with only studying commentaries on Torah. There is no replacement for actually hearing and reading aloud the perfect and immortal Word of G-d. Get together with other Jews, and participate in the public reading of the Torah. That is how the Torah will become rooted in your memory.

Quality #16:

“Through repetition” (be-mishnah)

Contemplation:

Although it is known as the ‘Oral Teaching’, and was passed down in unwritten form for untold centuries, the work which we call The Mishnah was compiled and written down around 200 CE by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who collected almost all the teachings of the scholars of his day and unified them into a single body of text. There are six ‘orders’ or volumes that comprise the Mishnah, each of which is made up of several tractates covering different subjects.

So is that the message for today? That the way to fully acquire Torah is through studying the Mishnah? Perhaps that is not the fullest understanding of this principle.

The word ‘mishnah’ means ‘copy’ or ‘repetition’. It comes from the root sheni, meaning ‘second one’. The king of Israel, as we discussed yesterday, was commanded to write a copy (mishnah) of the Torah and to read from it every day. He could not merely use his father’s copy; he had to make one himself. The act of copying, letter by letter, was a way to further engrave the Torah in his memory.

When you see words on a page, you remember them only so much. When you hear them read while looking at them, you retain more. When you teach the subject to others, you retain even more. And when you copy out the teaching, taking care to match every letter, the exact wording of the teaching will be firmly fixed in your mind.

The other meaning of mishnah, ‘repetition’, is the reason that the orally-transmitted halacha is called The Mishnah: it was passed down through the generations by mouth, and it was essential that the student should be able to recall it word for word so that it would remain unaltered. Thus, the process of handing down the halacha was called ‘repetition’ (mishnah), and those who taught it were called Tanna'im (‘repeaters’ in the Aramaic language).

Repetition is a tried and true method of memorization, and it can assist a person to analyze what he learns more deeply by drawing attention to precise wording.

So how do you acquire Torah? Read it aloud, repeat it, make a verbal or even a written copy of it.

Quality #17:

“With a limited amount of traveling / business” (be-mi’ut sechorah)

Contemplation:

This is sound advice: we tend to devote the extra time we have to the thing which we consider most important in our lives, and for some people, that could be work. We even call it our ‘occupation’, that which occupies our days and our thoughts. But if our business employment is truly our ‘occupation’, we risk losing sight of the things that are truly important – the things which our employment is supposed to support, not replace. Our family, our service to others, our Torah study, and encompassing and driving all of these, our relationship with G-d. As Jews, our only real ‘occupation’ is supposed to be the study, dissemination and practice of G-d’s Word. Everything else is just a side venture, an offshoot business.

But remember, mi’ut only means “a little”. It doesn’t mean “nothing”. It would be wrong for us to forgo our business endeavors entirely, not because we need them to survive (G-d could provide for us without our going out to work each day), but because our business endeavors are another way of serving G-d and spreading the light of the Torah. G-d put us into the world and commanded us to work in it, to improve it and to preserve it: “And the L-RD G-d took the Man, and set him down in the garden of Eden to work it and to safeguard it.” (Genesis 2:15). Therefore, when we perform a needful task for a customer and put in a good day’s work for our employer, we are fulfilling this mandate to labor for the benefit of the world. Our actions also reflect on the people we represent, on the Book by which we live, and on the One Who gave it to us.

“Holding your manner of life honorably among the Gentiles: that, in the very thing where they speak against you as evildoers, [yet] having witnessed your good works they may glorify G-d in the day of reckoning.” (1 Peter 2:12) “…But we beseech you, brethren, that ye increase more and more; and that ye earnestly strive to be quiet, and to do your own business, and to work with your own hands, even as we commanded you, that ye may walk respectably toward those who are outside, and that ye may have lack of nothing.” (1 Thessalonians 4:10–12)

The same thing goes for traveling. Some people make a lifestyle out of traveling and seeing the world; others only travel when they have a specific need that requires them to go to another place. Too much travel can wear out the body, wear down the mind, and wear thin the bonds of fellowship with your community. Limitations in traveling, as in so many things, can be a real benefit. And yet, to stay in one place your whole life is to miss many things which can enrich your understanding, broaden your perspective of the Torah’s words, and enable you to serve a wider audience. If the Holy Temple was standing (may it be rebuilt speedily and in our days!), we would all need to make an effort to travel three times a year to Jerusalem. Traveling is in our blood: we began our existence as a nation by walking into the desert for forty years.

So we should have a moderate amount of business dealings, and traveling as well. But we should definitely have some of it. Another way of translating the principle for today is that Torah is acquired “with a little bit of business and traveling”. Keep in mind this facet of mi’ut. It will come in handy over the next few days.

“I have seen the occupation which G-d hath given to the sons of Man to be exercised in it. He hath made every thing beautiful in its time: also He hath set the hidden eternal future in their heart, without which no man can find out the work that G-d does from the beginning to the end. I know that there is nothing better for them, than for one to rejoice, and to do good in his life; and also that every person should eat and drink, and enjoy the good of all his labour; it is the gift of G-d.” (Ecclesiastes 3:10–13) “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? he shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before obscure men.” (Proverbs 22:29)

Quality #18:

“With a little bit of common courtesy” (be-mi’ut derech eretz)

Contemplation:

Derech Eretz as business activity and ‘secular knowledge’:

Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888) became widely known for his outlook on Jewish studies, which was embodied in the phrase, “Torah with derech eretz”. He did not invent the phrase or the concept behind it; it is as old as the times of R’ Yishmael in the Mishnah (150 CE). But he breathed new life into the idea and championed it fearlessly and with enthusiasm. Some people took “Torah with derech eretz” to mean “Torah with secular studies”, and claimed that R’ Hirsch was in favor of secular (business-oriented) education. Others believed that it was encouraging a lifestyle of studying Torah while simultaneously earning a living.

Was R’ Hirsch in favor of learning the Torah alongside of ‘secular’ education? To answer that, we need to know what he believed about ‘secularism’. He rejected the notion that a person could or should learn Torah as just one of many philosophical subjects or works of literature. He believed firmly that Torah was not only unique and utterly different from all ‘philosophy’ or ‘literature’, but that every philosophy or work of literature should only be studied in the light of the Torah’s frame of reference. Torah is to be the lens through which we view all other educational subjects.

But precisely because of this, R’ Hirsch believed that philosophy, physics, mathematics, astronomy, biology, history, linguistics, literature, the arts and all other subjects were not ‘secular’ in their nature at all. Each one of them needed to be taught and learned, provided that it was through a Torah-founded framework. If done properly, they would be Torah subjects, not secular ones.

This put him into contrast with some of the Torah-observant leaders of his day, who believed that scientific education was inherently anti-Torah. R’ Hirsch believed that all science, properly studied, would lead to the further glorification of G-d. So too would all forms of business: the Torah’s instructions are given to a people who would be involved in many types of work, and it was meant to apply to them all.

This worldview, which encompasses all ‘worldly’ activity within the Torah’s sphere and encourages its development within that sphere, is what “Torah with derech eretz” meant to R’ Hirsch. If a man has raised sons who became merchants and shopkeepers and farmers and scientists rather than rabbis, he can hold his head up proudly so long as they are G-d fearing, Torah-observant merchants, shopkeepers, farmers and scientists – for the world needs those just as much as it needs rabbis.

Derech Eretz as moral decency and courtesy:

Our sages elsewhere in Pirkei Avos say that “derech eretz preceded the Torah by two thousand years” (Avos 2:2). Our patriarchs had no body of written laws and teachings of G-d to which they could refer. Their service of G-d was through the practice of derech eretz, morally decent behavior. They exemplified traits such as lovingkindness and hospitality, truth and justice. They opened their tents to strangers; they fed people; they dealt honestly in their business; they stood up for the oppressed and vulnerable. They treated people with respect and courtesy, even when those people had wronged them. That was derech eretz.

Earlier in Pirkei Avos, R’ Elazar ben Azariah says, “If there is no Torah, there is no derech eretz. If there is no derech eretz, there is no Torah.” (Avos 3:21) If a person has studied and become learned, what good does it do him unless he behaves in a decent, courteous and moral fashion? And if a person wishes to behave morally, how will he know the specifics of what to do and what to avoid, if he does not learn Torah? Torah and derech eretz truly go hand in hand.

Therefore, when the sages say here in Pirkei Avos that Torah is acquired with mi’ut derech eretz, it may be that they are warning not to let our sense of proportion slip. Our Torah study must constantly be seasoned with a bit of courtesy and decent behavior. Don’t get so wrapped up in your study that you fail to behave pleasantly with other people.

“One should always strive to be on the best terms with his brethren and his relatives and with all men and even with the heathen in the street, in order that he may be beloved above and well-liked below and be acceptable to his fellow creatures. It was related of R’ Yochanan ben Zakkai that no man ever gave him greeting first [without him pre-empting them], even a heathen in the street.” (Gemara, Berachos 17a) “Recompense to no man evil for evil. Provide things admirable in the sight of all men. If it be possible, as much as lies in your own selves, live in harmony with all men.” (Romans 12:17–18)

Quality #19:

“With a little bit of pleasure / enjoyment” (be-mi’ut ta’anug)

Contemplation:

The word for “enjoyment” here comes from the root oneg, meaning pleasure or delight, or a delicacy, perhaps of food. The concept of oneg is most well known to us from its preeminence during Shabbos. Oneg Shabbos (the enjoyment / pleasure of Shabbos) is an essential part of celebrating the holy day. G-d Himself tells us to “call the Sabbath a delight (oneg)” (Isaiah 58:13). We do so in part by eating rich foods and delicacies, and engaging in other activities which bring delight to our Shabbos table such as singing zemiros (songs, hymns).

Since we set aside Shabbos as a time for oneg, it is only proper that we should not indulge constantly in it during the rest of the week. Pleasures which are indulged in every day soon cease to be special. It is also a well known medical fact that constant eating of delicacies is bad for your health. In this context, “a limited amount of pleasure / delicacies” seems to be sound advice. If the body is unhealthy, the mind will also have difficulty focusing and learning.

But remember, a little is not the same as nothing. We may not omit oneg from our lives altogether. Today’s lesson cautions us against asceticism as well as hedonism. We are supposed to take our learning with “a little bit of enjoyment” from time to time.

Quality #20:

“With a little bit of sleep” (be-mi’ut shenah)

(With acknowledgements and gratitude to Rabbi Avraham J. Twerski, from whose book, ‘Visions of the Fathers’, large portions of tonight’s commentary were drawn.)

Contemplation:

Yet on the other hand, too much sleep can detract from your mental sharpness as well. Rising early in the morning is not simply a laudable practice associated with industriousness and diligence; it is also a healthy time to wake up. Your body and mind will feel clearer and more rested if you make a habit of rising early, and it is the perfect time to spend studying some Torah before anything else intrudes on your day.

Some Torah scholars are famous for having slept barely at all. The Vilna Gaon, a prodigious genius and a giant in the Torah world, slept an average of twenty minutes in a day, in a series of catnaps. He used to keep a bucket of cold water by his feet while studying, so that if he started to feel drowsy, he would put his feet into the water to help himself stay alert, so intent was he on not wasting a moment when he could be studying Torah. Was he damaging his health by acting this way? Or are we all required to follow his example?

The Tzaddik of Sanz, another rabbi who slept very little, offered the following explanation for his unusual behavior: “A swift runner may cover a long distance in a fraction of the time it would take the average person to travel that far. I happen to be a swift sleeper. I can accomplish in minutes of sleep what may take others hours.”

We may all have experienced, at one time or another, a night of little sleep which nevertheless left us feeling refreshed upon waking. Sometimes, a little sleep accomplishes more than we expect it to. In modern scientific jargon, the REM (rapid-eye-movement) phase of sleep is believed to be the most important part of a night’s rest, and the length of time it takes for the body to enter REM sleep (sometimes several hours) is the most critical factor in determining how long the night’s rest needs to be. If a person could enter REM sleep immediately upon falling asleep, he could theoretically be refreshed with far fewer hours of sleep.

This is what the Tzaddik of Sanz meant. Such a rigorous schedule as the Vilna Gaon’s is not meant for everyone nor would it be healthy for everyone; only a very few people may find that they have been gifted, genetically or otherwise, with less of a need for sleep. The important thing is that, once a person has had enough sleep to be refreshed, he does not develop a habit of lying in bed longer than he has to. This habit of indolence leads to poverty, both physical and mental:

“By the field of the slothful man I passed, and by the vineyard of the person lacking heart. And, lo, it was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered its surface, and its stone wall was broken down. Then I saw, and I myself applied it to my own heart: I looked, and I received correction. ‘A little sleep (m’at shenot), a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to lie down’: and your poverty shall come walking along, and your want as an armed man.” (Proverbs 24:30–34)

Here, “a little sleep” is used in the words of the slothful man, to indicate his plea for ‘just a little more sleep’. A ‘little more’ is open-ended. No matter how much he has, he always wants ‘a little more’. That is the sign of an addiction. In all the instances we have looked at where the word mi’ut is used, it refers to moderation and keeping something in its proper proportion. To become addicted to anything, whether it be work, pleasure, worldly business, or sleep, is to surrender our freedom of moral choice and to become slaves to a passion or a habit.